Overview and takeaways on Chinese commercial activity in the Middle East and beyond #1

15 Jan - 4 Feb 2022

CONTENTS

1) Attendance of High Profile Middle Eastern Leaders at Beijing 2022 Signifies Deepening Bilateral Ties

2) Gulf FMs Arrive in Beijing in ‘Positive’ Push for China-GCC FTA Talks Amid Wider Push for De-Dollarization of Trade

3) Beijing’s Increased Economic Footprint in Iraq and Geopolitical Rivalries

4) China’s Dominance in Clean Energy Metals

5) Chinese Manufacturers Step in to Fill Middle Eastern Demand for Military Drones

6) Syria Courts Belt and Road Investments

1) Attendance of High Profile Middle Eastern Leaders at Beijing 2022 Signifies Deepening Bilateral Ties

We highlight the significance of the four Middle East leaders attending namely, Abel Fattah al-Sisi (Egypt), Mohammed bin Salman (Saudi Arabia), Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani (Qatar) and Mohamed bin Zayed (UAE). All four countries occupy a significant place under China’s Belt and Road Initiative as they are among the top Chinese trading partners in the Middle East.

1) China is already running large trade deals with many of the countries represented above.

2) No sign of major western leaders amid heightened diplomatic tensions

3) Major geopolitical developments of late are centered around Chinese commodity needs; as highlighted by the fact that many leaders in attendance represent some of the biggest commodity producers in the world.

Contrary to popular belief that China-Middle East ties hinge only on energy imports, China does run a trade surplus with the Middle East, having exported USD 144 billion worth of products vs US$128bn of imports in 2020. Aside from energy cooperation, China has also committed significant investments in infrastructure, industrials, and financing in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE over the past several years. We see this development only gaining steam as the US draws down its political and economic footprint in the Middle East.

2) Gulf FMs Arrive in Beijing in ‘Positive’ Push for China-GCC FTA Talks Amid Wider Push for De-Dollarization of Trade

Coincidently, we saw Beijing receive a high-level GCC delegation in early January to discuss the China-GCC FTA, which has been in negotiations since 2004 (suspended over the Syrian conflict). However, geopolitical developments in 2021 have injected new urgency into China’s efforts to strengthen its economic ties with the bloc.

1) Washington’s receding economic, political, and military role in the Middle East

2) GCC rapprochement with Qatar, thus allowing the bloc to negotiate on a united front

3) China’s 25-year cooperation agreement with Iran. The GCC itself seeks to encourage Iranian engagement with the outside world to reduce risks of regional hostilities and attacks on oil infrastructure. Several visits by high-profile GCC leaders to Tehran in recent months signal a shift away from hawkish stances on Iran taken due to regional geopolitical rivalries and US pressure. The UAE’s status as an entrepot for Iranian trade and capital flows allow Abu Dhabi to benefit from Tehran’s increased engagement with the world (regardless of whether this includes the US and its allies). It’s noteworthy that the Iranian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Hossein Amir Abdollahian, arrived in Beijing on the same day that the GCC delegation wrapped up their visit.

4) China’s growing energy requirements, especially considering the most recent domestic power outages and soaring energy prices. The GCC recognizes that China is a far more significant oil importer than the US now.

It is interesting that China’s crude oil imports dropped for the first time in 20 years, yet oil prices rose as much as they did in 2021. Much of the drop was attributed Chinese government attempts to crack down on excessive imports by petroleum refiners, but a rebound of imports in December 2021 as refiners rushed to fill annual quotas as energy shortages intensified may influence Beijing to increase annual quotas in 2022. If we see Chinese imports revert back to previous levels in 2022, this would seem to be quite bullish for oil and gas prices.

At a macro level, we are also likely to see multi-currency energy pricing gain more traction, much of it stemming from China’s economic needs. Over time China seeks to reduce the dependency on USD to buy oil globally, resulting in less USD demand in the longer term. China has already launched initiatives to conduct Renminbi-denominated trade with several Middle Eastern partners, although this remains at a nascent stage.

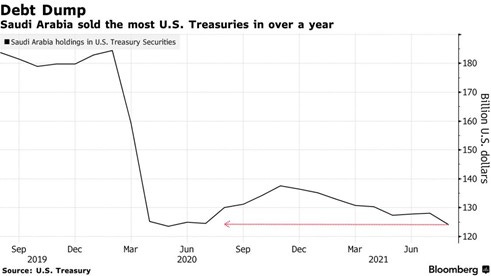

We are already starting to observe this trend in China’s strategic partners, most notably Russia, which decreased its Central Bank forex reserves’ dollar weighting (22% to 16%) and increased its Yuan weighting (12% to 13%) at the beginning of 2022. Some of China’s biggest Middle Eastern partners have made similar moves, most notably Saudi Arabia. Historically, Saudi Arabia recycled USD from oil sales into purchasing more US Treasuries and financial assets as oil prices rose. However interestingly, the Kingdom has sold a significant amount of US Treasuries since early 2020. We can speculate at the reasons for making that decision, but perhaps a signal of taking a more active approach when it comes the Kingdom’s regional and sovereign interests given the West’s waning influence.

In similar vein, we do believe there will be more exchanging of Chinese investment for commodities (e.g. oil, infrastructure, and food&ag) and Yuan-based transactions among China’s biggest trading partners in the Arab world, most of which are the among the world’s most important oil producing countries.

3) Beijing’s Increased Economic Footprint in Iraq and Geopolitical Rivalries

In late January 2022, we saw significant public outcry in Iraq over delayed Chinese projects in the country, with netizens blaming the US and its regional allies for undermining Iraqi efforts to diversify international investment in the country. The hashtags #ثورة_الحرير_قادمة (Silk revolution is coming) and #طريق_الحرير_مطلبنا (Silk road is our demand) trended with thousands of retweets, matched by small scale street protests in the south of the country. Many key influencers attributed the delays to pressure by other countries seeking to cash in on Iraq’s oil boom by winning lucrative infrastructure deals. These users claimed that the deals offered by these states were predatory and politicized, and were significantly smaller in scale than proposed Chinese investments linked to the Belt and Road Initiative. These claims have been propagated by Iranian-backed militias in Iraq which have called for the activation of an Iraqi-Chinese “oil for reconstruction” agreement dating back to September 2019. The 20-year agreement has not been implemented as many anti-Iranian factions felt it entailed mortgaging the country’s oil wealth to the Chinese and their Iranian allies for two decades.

Local politics aside, China is becoming an increasingly significant economic actor in the country. Iraq has long been one a key oil supplier to China, accounting of USD 19.2 billion in imports in 2020, or 10.9% of the total. Iraq imported approximately USD 9.5 billion of Chinese goods in 2019 (19% of total). Iraq was the top target for China’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2021, receiving USD 10.5 billion in financing for infrastructure projects including a heavy oil power plant. China and Iraq are cooperating to build the USD 5 billion Al-Khairat heavy oil power plant in Karbala province and Sinopec (306.HK) has won the contract to develop Iraq’s Mansuriya gas field near the Iranian border. The two countries are also cooperating on an airport, solar, petrochemical, school-building, and other projects. Electricity, transport, and education projects by Chinese companies are particularly popular in Iraq, where these sectors are beset with severe structural and conflict-related challenges. While much of the public in Iraq is under no illusions that Chinese companies are primarily interested in profit, China is seen as a less politicized and more efficient partner than most of its peers.

A study published by Fudan University showed that Iraq become the third-biggest partner in Belt and Road Initiative for energy engagement since 2013, after Pakistan and Russia. This tracks with a broader trend in Belt and Road investments, which have recently shifted from Southeast Asia to the Middle East, as illustrated by this graphic from the Financial Times based of the Fudan study.

4) China’s Dominance in Clean Energy Metals

https://elements.visualcapitalist.com/visualizing-chinas-dominance-in-clean-energy-metals/

China is well ahead of the supply chain race in the transition towards a clean energy future. Interestingly, we find China Molybdenum (3993 HK) [CMOC], Tianqi Lithium (002466.SZ), and Zijin Mining (2899.HK) as good options for exposure in the clean energy metals space, all of which have also made significant upstream acquisitions in the producing countries highlighted above.

We hone in on CMOC, which issued a 2021 profit alert last month, with full year net profit estimated to rise from CNY 2.4-2.8bn to CNY 4.7-5.1bn, reflecting 92-101% of consensus estimates.

We note that CMOC’s copper/cobalt production volumes were up 15/20% yoy to 209/18.5kt in 2021 owing to its 10kt expansion project in Tenke, Democratic Republic of Congo. CMOC output guidance for 2022, particularly its copper and cobalt mine in Congo expects to see significantly increased output additions from a full year of operations (the Congo mine was put into operation in July 2021), while tungsten and molybdenum output in China are expected to decline. Niobium and phosphate output from its Brazil operations were guided to remain broadly stable.

The stock trades at an inexpensive 12x blended forward P/E ratio and in an environment of elevated commodity prices, volume growth should be conducive to earnings growth.

5) Chinese Manufacturers Step in to Fill Middle Eastern Demand for Military Drones

A visit by Saudi Defense Minister, Khalid Bin Salman, to Beijing in January 2020 suggested deepening bilateral military ties. Given China’s small (but growing) military footprint in the region, we see this playing out more in the arms export space in the near term. Chinese manufacturers may be filling a void left by Washington’s reluctance to sell drones to key Gulf partners. The US, along with several key EU suppliers have halted exports of combat drones to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, due to public outcry over the high civilian death toll resulting from these countries’ interventions in Yemen and Libya. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) released a report in March 2021, nothing that while arms transfers to the Middle East between 2016 and 2020 had increased by 25%. As noted, Chinese companies are seeking to replace reluctant western suppliers for a range of high-tech military hardware. The Aviation Industry Corporation of China, China Electronics Technology Group Corporation, China North Industries Group Corporation, and China South Industries Group Corporation – appear to be significant players in this space. According to SIPRI data, between 2016 and 2020, increased the volume of arms transfers to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates by 386% and 169%, respectively, compared to 2011-2015. However, this must be interpreted with the understanding that sales started from a low base.

Chinese companies have delivered approximately 220 armed drones to 16 countries, mainly in the Middle East and Africa. These drones are becoming increasingly sophisticated and while still not in direct competition with the most advanced US models, present a more cost-effective solution. For example the Wing Loong 2 has been primarily designed and developed for export at a cost of USD 1-2 million, compared to the Predator at USD 4 million, or the MQ-9 Reaper at USD 30 million. Chinese drone manufacturers appear to be cashing in on a US/EU reluctance to sell Middle Eastern states such hardware, albeit at a relatively small scale. As Chinese technology improves and the significance of western diplomatic pressure against purchasing such hardware wanes, this trend is likely to become more pronounced. Chinese drone manufacturers and the governments they supply are secretive about deal figures, but we have attempted to summarize the Middle Eastern acquisitions through the following graphic based off local language news reports and imagery analysis.

6) Syria Courts Belt and Road Investments

In January 2022, the Syrian government signed an MOU to join China’s Belt and Road Initiative in a bid to secure funding for reconstructing following the devastating civil war dating back to 2011. Media outlets quoted various experts, who suggested that the Assad regime was seeking to break out of diplomatic isolation while China sought to gain additional energy sources. Increased Chinese influence in Syria gives it increased leverage over export routes from Iraq, where more than 10% of Chinese oil imports originate from. Overall 46-47% of Chinese oil imports come from the Middle East. China has previously vetoed several UN resolutions targeting the Assad regime, and in 2016 provided the regime with limited training and humanitarian assistance. At present bilateral trade is minor, totaling just USD 1.3 billion in 2019 according to China’s Ministry of Commerce. The financial returns of any future investments are likely to be slim due to the dire state of the country’s infrastructure and finances.

Assad may be courting China as to counter overreliance on Moscow, as the former as reportedly unhappy with Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to Damascus in July 21. While there has been extensive talk of Chinese-backed free trade zones and pipelines in Syria, limited concrete detail has emerged and for now, the recent diplomatic flurry may be more symbolic in nature. One thing is for sure, the region’s governments are increasingly looking to China and Russia over the US and EU states for economic, military, and political backing.

Very well researched and great information. Liked and subscribed!

Great read. Subscribed.