The Chinese Polysilicon Industry: Navigating overcapacity toward brighter horizons

Unpacking supply gluts, demand surges and Beijing’s anti-involution push

While overcapacity narratives dominate Western views of Chinese solar stocks, often fueled by short-term politics and fear, the reality is more nuanced. Solar demand isn’t just growing; it’s exploding in unexpected places, outpacing even optimistic projections. There’s also a tendency to paint the whole industry with the same brush, but in reality each production stage comes with its own supply and demand dynamics.

This piece challenges these narratives by focusing on the lynchpin: polysilicon, which is entering a phase of consolidation after a well-publicized supply glut.

If you track the energy transition, you may have seen the fundamentals analysis of key polysilicon player Daqo New Energy (DQ.N; “Daqo”) from DeepValue Capital last year. Daqo currently boasts a market cap of ~USD 2.2 billion, and the piece sums up the the Company as an undervalued investment opportunity, emphasizing its rock-bottom costs, cash-rich balance sheet, and positioning to thrive as industry cycles turn upward amid bankruptcies of weaker players.

We’re also drawing from Taro Sakamoto’s Apeconomics (paywalled) insightful take on the Company, which also dives into China’s push for polysilicon consolidation and managed pricing to curb overcapacity (a lingering issue in the wider supply chain). The analysis highlights how government-backed funds could reshape the sector and favor efficient survivors like Daqo.

Adding to the good work already done in this space, we compile the numbers that showcase why demand could close the gap faster than expected, especially as emerging markets drive adoption, and how Beijing’s reforms accelerate the shakeout. That said, Chinese solar isn’t risk free with tariffs, sanctions and policy shifts loom. But for those willing to look beyond the headlines, we add further color as to why the industry giants appear well-equipped to navigate industry headwinds.

Current state: Surging demand yet to close the overcapacity gap

Even the most pessimistic observers wouldn’t deny that end user demand for solar power is booming. It’s emerging as the most cost effective renewable in most use cases, and probably the easiest for individuals and businesses to independently install.

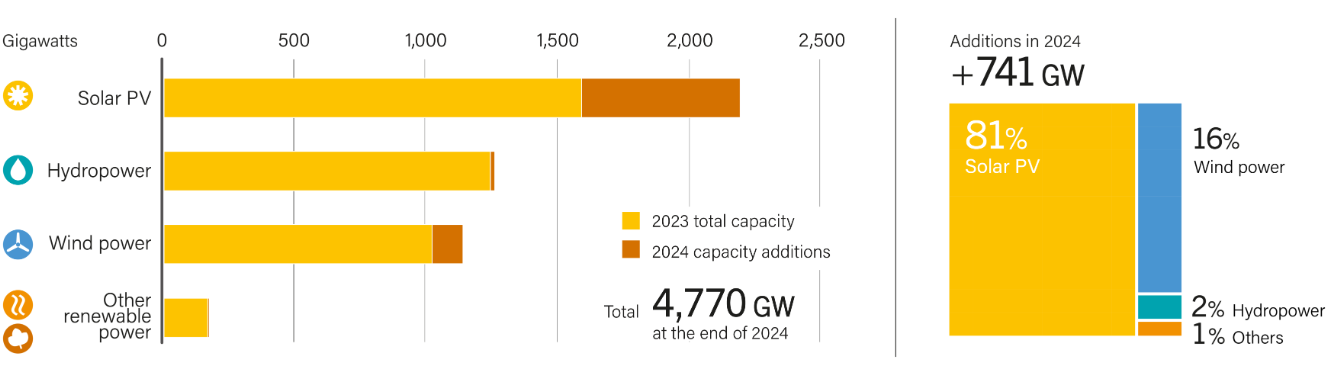

Global cumulative solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity surged from around 230 GW in 2015 to over 2,200 GW by end-2024, a CAGR of about 29% and nearly a tenfold increase in a decade. Recent years have been even more dramatic: Annual additions in 2023-2024 matched or exceeded the entire global fleet from just a few years prior.

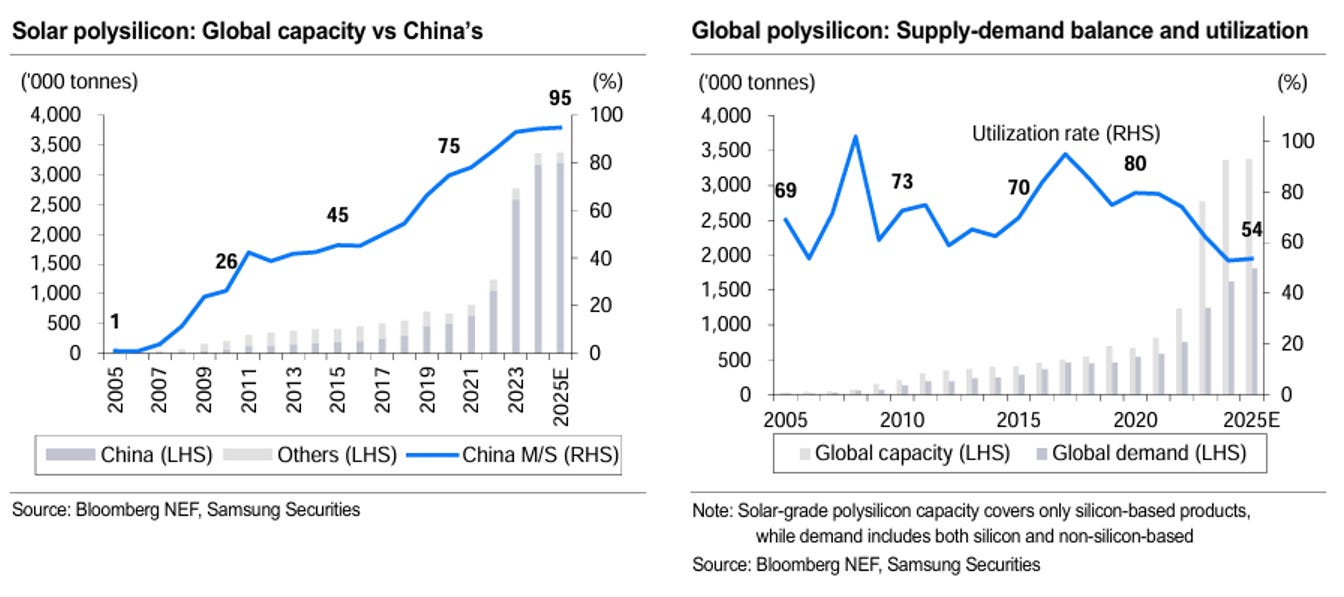

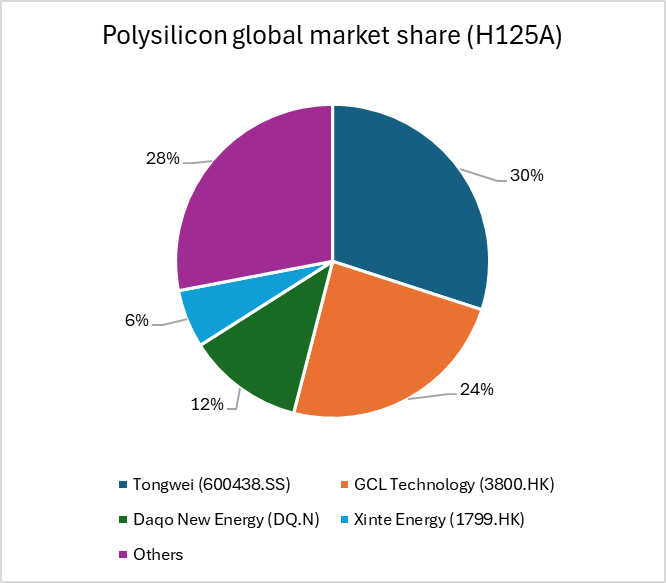

China has a powerful grip on solar power, supplying 80% of the world’s panels and 93.5% of global polysilicon production in 2025. The vast majority of polysilicon production goes into solar, so all in all Chinese companies control the key raw material fueling this boom.

The polysilicon industry, powered by subsidies and private capital chasing demand, has built capacity outpacing actual needs. Global polysilicon nameplate capacity (fixed installed potential) is expected to hit around 3.5 million tonnes (MT) in 2025, while effective demand (tied to PV installs) hovered at 1.5-2.4 MT, driving utilization down to 50-60%.

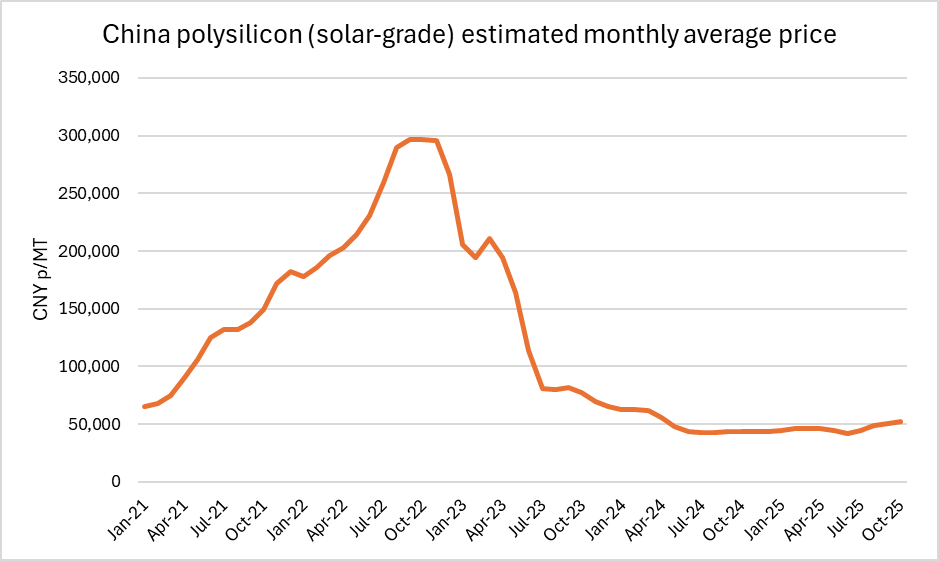

This glut crushed polysilicon prices, falling dramatically from over ~ CNY 200,000 (~USD 28,000) p/MT in early 2023 to ~ CNY 42,000 (~USD 5,900) p/MT mid-2025, before rebounding to CNY 52,000 (~USD 7,300) p/MT as of October 2025. Chinese firms have been forced to dump below cost amid expanding polysilicon capacity and maintain market share, thereby significantly eroding profits.

Since early 2024, average production capacity utilization has collapsed from 98% to below 40%, forcing half of the industry’s major companies (9 out of 18) to halt production. This has led to a 44% yoy decline in domestic output in H125. The industry’s inability to form a cohesive cartel to manage supply, due to divergent interests and downstream fragmentation, underscores the intensity of the competitive pressures and the absence of a near-term self-correcting mechanism.

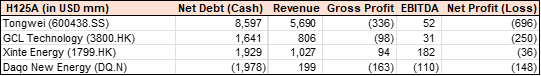

The financial toll became evident in the first half of 2025 with the leading listed Chinese players in the space continuing to report significant net losses. Low utilization hiked per-unit costs, turning a once-profitable sector into a money pit despite China’s solar dominance.

Solar demand is only accelerating with surprise bright spots

DeepValue Capital’s thesis alludes to the broad tailwind of growing demand for polysilicon’s core end-use – solar panels.

“Despite this bleak picture, the average of 5 industry forecasts suggest demand will grow by about 12.8% per year globally.”

We see this tailwind as underappreciated in the broader market, especially with headline-grabbing demand surprises from the developing world, where solar adoption isn’t optional but essential.

Taking a global view first, growth in solar PV capacity isn’t linear; it’s consistently smashing forecasts due to plummeting costs (down 90% since 2010), energy crises, and net-zero goals. The IEA now projects 4,600 GW of renewables added from 2025-2030, with solar PV claiming 80%. Similar bullishness can be derived from BNEF which sees 2025 installs at similar levels, building to near 1 TW/year by 2030, while SolarPower Europe tallied 597 GW added in 2024, is now forecasting up to 930 GW annually by 2029.

This isn’t just policy-driven; in frontier markets, it’s consumer-led. Dirt-cheap panels enable leapfrogging unreliable grids, much like mobile phones obviated the need for expensive landline infrastructure in many developing markets. In Africa and Asia, landline penetration stalled at 10-20%, while mobiles hit 80-90% by 2010. Solar appears to be following suit: No waiting for shaky state grids, households are now installing panels for immediate, affordable power.

Take Pakistan’s “solar revolution”: Frustrated by 155% electricity bill hikes and blackouts, consumers imported 17 GW of panels in 2024, more than the US or Germany, making it the world’s third-largest importer globally and number one across emerging markets. Similar dynamics brew in Nigeria, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and the Philippines, where patchy supply and high costs push self-reliance.

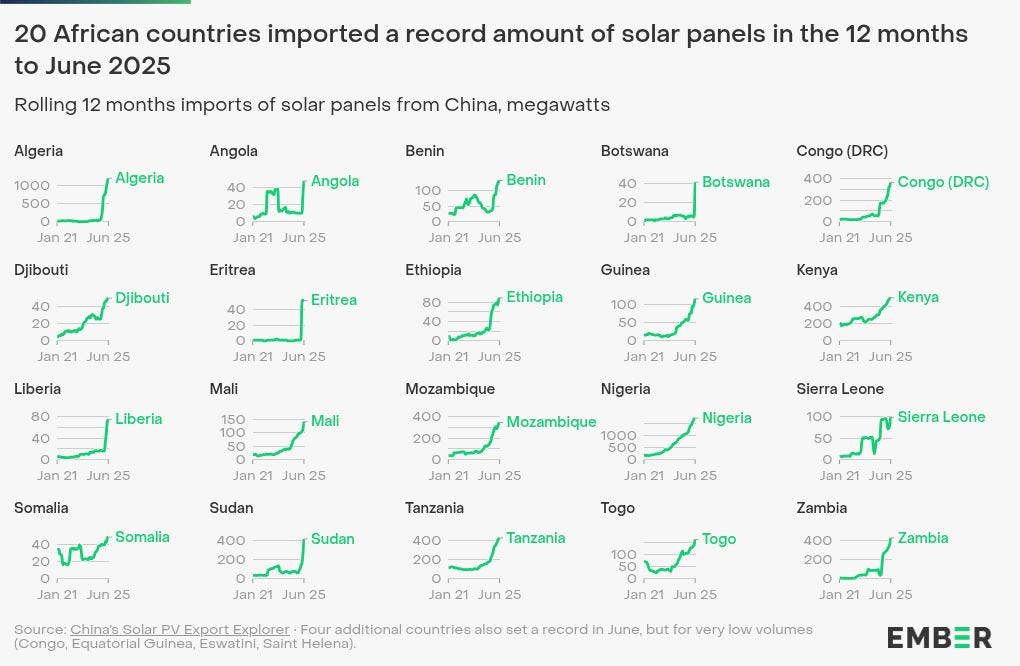

Africa’s growth is only just picking up, and the trajectory may prove even more striking. Imports from China were up 60% yoy in June 2025. The continent added 12x more solar in 2023 than the prior decade’s total, with rooftop installs doubling and utility projects booming. With 600 million lacking electricity, USD 5.7 billion in financing (up 50% yoy), and costs down 80% in 18 countries via tenders, solar could grab 40% of Africa’s USD 100 billion energy spend by 2030.

Where surging demand meets supply: The polysilicon bottleneck

Overcapacity talk often fixates on panel assembly lines but often lumps upstream polysilicon production in with this. While the polysilicon industry may currently face overcapacity, when we break down the numbers this seems unlikely to persist as demand will catch up quicker here than for downstream panel makers.

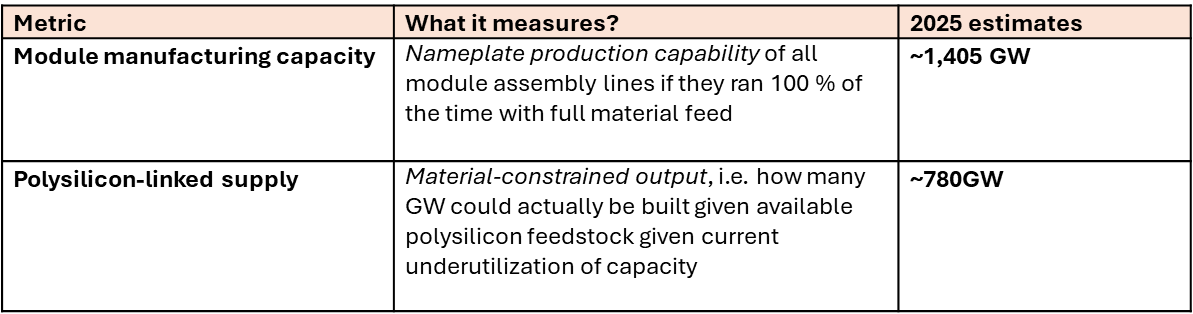

While the world’s solar panel factories have a theoretical estimated module manufacturing capacity of ~1,405 GW p/annum (if running 24/7 with unlimited materials), the actual limit is set by the availability of polysilicon, the key raw material for over 95% of panels.

With nameplate capacity of 3.5 million MT of polysilicon globally this year, and modern manufacturing using just 2.1-2.5 grams p/watt of panel power, this caps real-world buildable panels at around 1,400-1,670 GW in theory.

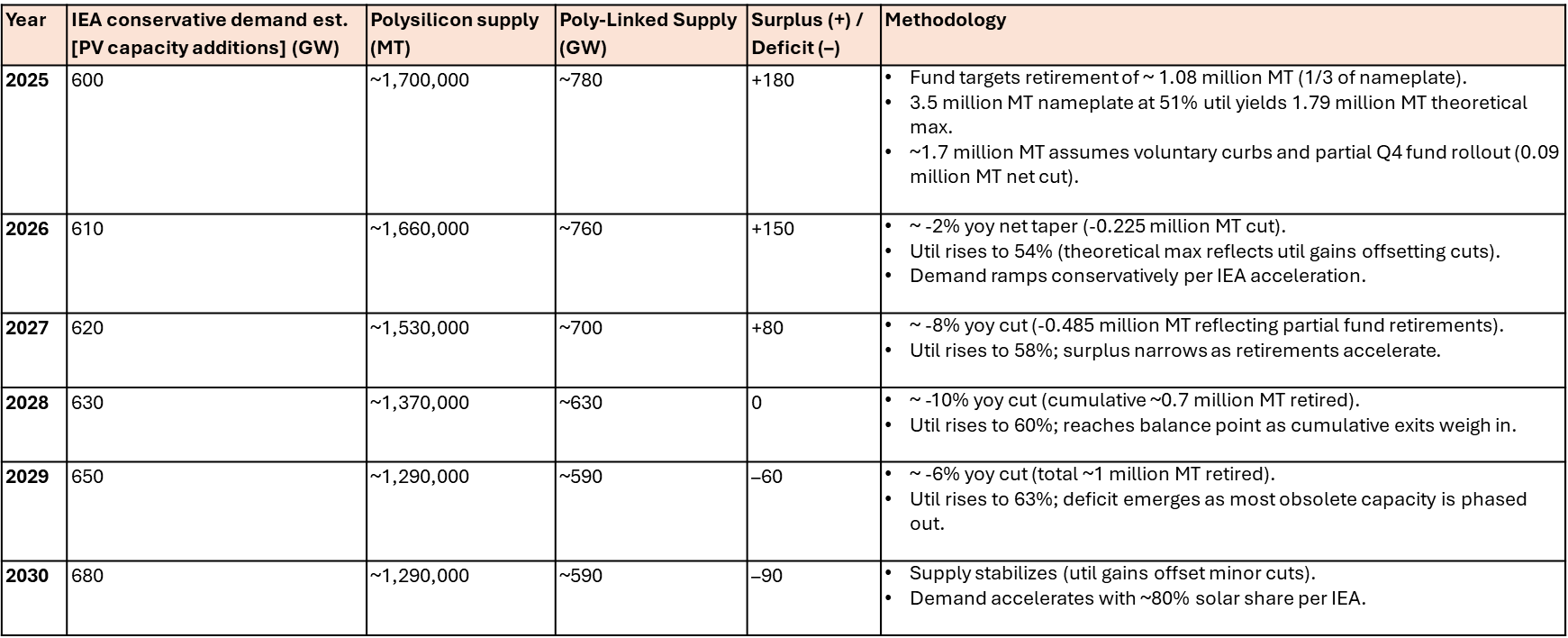

But in practice, it’s much lower (~780 GW) due to polysilicon factories shuttering production capacity amid oversupply. To forecast when supply and demand align, it’s best to think in “polysilicon-equivalent GW”, focusing on this upstream constraint rather than downstream factory hype.

Even with the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) track record of consistently underestimating of demand growth (which contradicts conservative industry estimates of 10-15%), we see a convergence of polysilicon supply and end user demand for solar panels.

Based on our adapted estimates, we tend to align with the view that mild oversupply is anticipated to linger through 2027, with poly-demand convergence expected by 2028, preceding full module resolution, with potential shortfalls in 2029-2030 should demand accelerate, with upside coming from the Global South and stalled production investments. The key risks to this are the delayed rollout state-led of capacity restrictions, US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) tariffs and slower adoption if the cost of traditional fuels falls further.

Wheat to be separated from the chaff amid government reforms and industry shakeout

Beijing’s “supply-side reform 3.0” (starting 2026) targets “involution” across manufacturing, with polysilicon as a focal point via energy controls, self-regulation, and below-cost bidding curbs. The Chinese government’s anti-involution push, launched July 1, 2025, echoes 2016 reforms.

At the end of July 2025, Caixin had reported major producers were working towards developing a proposed CNY 50 billion (USD 6.4 billion) fund aimed at retiring over 1 million MT of obsolete capacity (from 3.5 million MT total), endorsed by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. While no specific timeline and hard details was attached to this, the fund rollout launch was expected in Q325 with purchases starting in Q425. Cutting a third of Chinese PV production capacity could increase the global polysilicon utilization rate up to 78%.

Furthermore, the Chinese government is advancing its polysilicon sector reforms through two key regulatory drafts over the past two months. On September 5, 2025, the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) released for public comment a proposed update to the “Norm of Energy Consumption per Unit Production of Polysilicon and Germanium”, aiming to impose stricter energy efficiency limits for the polysilicon segment.

This was followed on October 9, 2025, by a joint draft amendment from the NDRC and SAMR announced a draft amendment on curbing disorderly price competition, which specifically targeted the prevention of “below-cost bidding” and other forms of disorderly pricing. The measure is designed to establish clearer rules for market price order and curb cut-throat competition.

Concurrently with these regulatory moves, industry players are taking action. On October 10, 2025, GCL Technology (3800.HK; “GCL”) announced it had completed the first closing of a private placement, raising approximately USD 700 million, with 33% of the net proceeds to be used directly for “structural adjustment of the polysilicon production capacity,” directly validating the ongoing industry-wide consolidation.

Consolidation favors the efficient in this market; Q325 results recap

China’s polysilicon consolidates around low-cost leaders, with the top five holding over 80% of output.

Driven by the rebound in polysilicon prices and industry-wide “self-discipline”, the four major Chinese polysilicon producers showed marked sequential improvements in Q325, with profitability metrics initially turning positive across the board.

Tongwei (600438.SS; market cap: ~USD 15.4 billion): While revenues dipped 2% yoy to ~USD 3.4 billion, the Company’s operating margin saw improvement and operating cashflow turned positive at ~USD 67 million, a sharp reversal from the previous quarter, attributed to polysilicon price rebound amid self discipline. However, net loss widened to ~USD 44 million [Stock: ~ +17% post-earnings (as of November 7, 2025)].

GCL Technology (3800.HK; market cap: ~USD 5.4 billion): Revenue grew 31% yoy to ~USD 198 million with EBITDA turning positive and PV materials segment showing a profit of ~USD 135 million (boosted by disposal gains) [Stock: ~ +11% post-earnings (as of November 7, 2025)].

Daqo New Energy (DQ.N; market cap: ~USD 2.2 billion): The Company staged a strong financial recovery with revenue up 23% yoy to ~USD 245 million. It returned to positive EBITDA of ~USD 40 million and its net loss narrowed substantially to ~USD 15 million [Stock: ~ +29% post-earnings (as of November 7, 2025)].

Xinte Energy (1799.HK; “Xinte”; market cap: ~USD 1.6 billion): The Company showcased a strong annual recovery, narrowing its net loss by 82% yoy to ~USD 38 million despite an 8% drop in revenue. This result, however, moderated from the sequential profit of ~USD 6.7 million seen in Q225 [Stock: ~ +10% post-earnings (as of November 7, 2025)].

China steel industry parallel provides transitionary blueprint

China’s steel industry provides a compelling blueprint for how polysilicon could turn around amid its current overcapacity crisis. Back in 2015, the sector faced a similar glut: nameplate capacity hit 1.2 billion MT against demand of just 800 million MT, driving prices down by 56% and plunging many firms into losses.

This “involution” with competition fueled by state-backed expansions mirrors today’s polysilicon market, where rapid buildouts have led to utilization rates as low as 50-60% and prices crashing over 80% since 2023.

The reforms, rolled out from 2015 to 2020 under Beijing’s supply-side initiative, targeted the root causes. Capacity was slashed by 150 million MT (12-15% reduction) through enforced shutdowns of inefficient plants, stricter environmental standards, and consolidation around stronger players. The outcomes were transformative with industry utilization rising from 70% to 78% and prices rebounding 116% between 2016 and 2017, and industry profitability swung from operating losses to gains. Government enforcement was key, with penalties for non-compliance and incentives for survivors, ultimately reshaping the market into a more sustainable structure.

Polysilicon shares striking parallels. Both industries suffered from state-supported booms that bred overinvestment and price wars. Just as steel’s utilization improved post-cuts, polysilicon could see the same transformation with Beijing’s role in enforcing exits via anti-involution measures would similarly boost remaining leaders.

However, a key difference favors polysilicon: While steel demand merely stabilized after reforms, polysilicon benefits from explosive solar growth, PV module additions led by the Global South over the next 3-5 years potentially accelerating recovery. If polysilicon follows steel’s path, prices could double within 1-2 years once restructuring gains traction, rewarding efficient survivors and easing the sector’s pain.

Structural reforms improving equity quality and to drive re-ratings

DeepValue Capital’s deep dive on Daqo and Apeconomics’ reform analysis highlight intriguing tailwinds, but our broader view suggests that if industry compliance with anti-involution measures strengthens and supply-demand convergence materializes as projected, well-positioned polysilicon firms could see a meaningful re-rating. With the sector trading at secular lows amid cycle-bottom conditions, polysilicon prices down over 75% since 2023 and valuations compressed, this presents an opportunity for exposure at potentially attractive entry points if you believe the upturn unfolds, which we tend to believe so. As an upstream segment, polysilicon stands to benefit indirectly from downstream surges in Global South demand through increased panel exports and sales that boost polysilicon consumption, amplifying revenue look-through for efficient producers.

Leaders like Tongwei, GCL, Daqo and Xinte show resilience in the shakeout, with Q325 reports indicating momentum. As we highlighted above, Tongwei and GCL reported margin improvements on price stabilization, while Daqo swung to positive EBITDA.

Broader policy shifts, including legal and regulatory pushes for enhanced shareholder returns via dividends and buybacks among listed companies, add to the upside, which could potentially mark the start of a new bull phase for Chinese equities if anti-involution drives sustained capacity rationalization across sectors like polysilicon. Only time will tell whether we’ve bottomed out in this cycle.

Key risks do remain, such as delayed fund implementation, UFLPA tariffs disrupting exports, or slower emerging-market adoption tempering demand growth.

We hold a small position in one of the players the polysilicon industry.

Disclaimer: This research piece above is for informational, entertainment, educational, and/or study or research purposes only. The information contained herein or discussed does not, should not, and cannot be construed as or relied upon and, for all intents and purposes, does not constitute or provide professional financial, investment, or any other form of advice. This research does not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any securities or any other financial instruments in any jurisdiction, including where such actions are illegal. This research is not intended for publication in jurisdictions where it would violate laws. The research does not consider individual investment objectives or financial positions and merely expresses the opinions of its authors. Any investment involves taking substantial risks, including (but not limited to) the complete loss of capital. Every investor has different strategies, risk tolerances, and time frames. You are advised to perform your own independent checks, research, or study, and you should consult a licensed professional before making any investment decisions. The assumptions and parameters discussed or used are not the only reasonable ones, and no guarantee is given for their accuracy, completeness, or reasonableness. No promise is made that any indicative performance return will be achieved. The research is derived from public information sourced by Pyramids and Pagodas. No representation or warranty is given for the reliability, completeness, timeliness, accuracy, or fitness of this research, nor is any responsibility or liability accepted for any loss or damage. The authors (Pyramids and Pagodas) shall in no event be held liable to any party for any direct, indirect, punitive, special, incidental, or consequential damages arising directly or indirectly from the use of any of this material.