Will the recent pivot in Turkey’s monetary policy halt the Lira’s downward spiral?

Interest rate hikes provide tentative relief for investors disappointed by the country’s anti-climactic growth story, but deeper and more painful reforms are needed.

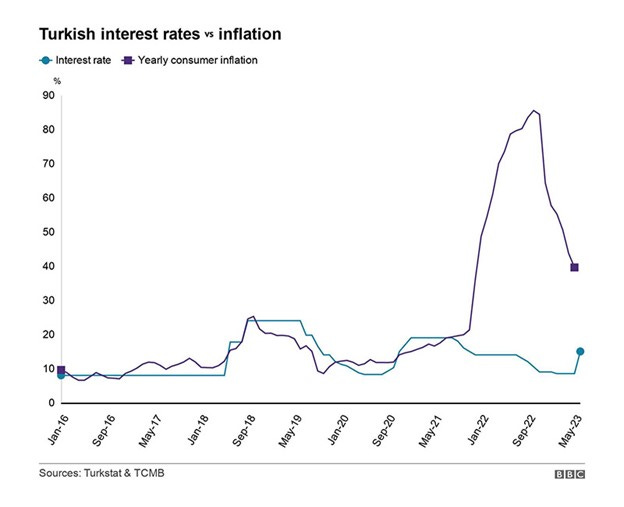

On 22 June 2023, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (CBRT) rose interest rates from 8.5% to 15%, a long-awaited move that may signal a shift to more orthodox policy aimed at taming soaring inflation. The decision came shortly after president Recep Tayyip Erdogan secured a third term in office, defeating a more unified opposition and giving him an emboldened mandate to tackle the country’s ongoing cost of living crisis and plummeting lira exchange rate.

Turkey has been one of the fastest-growing economies in the world since the early 2000s, despite facing some challenges in its monetary policy. According to the World Bank, Turkey's per capita GDP increased from less than 40% of the OECD average in the mid-2000s to more than 60% in 2019. This growth was driven by productivity gains, foreign investment, and social inclusion. The country enjoys a comparative advantage in its exports, due to its proximity and free trade policies with the EU. Its manufacturing sector has held up well amid the headwinds and occupies a share of GDP similar to industry in China and Malaysia.

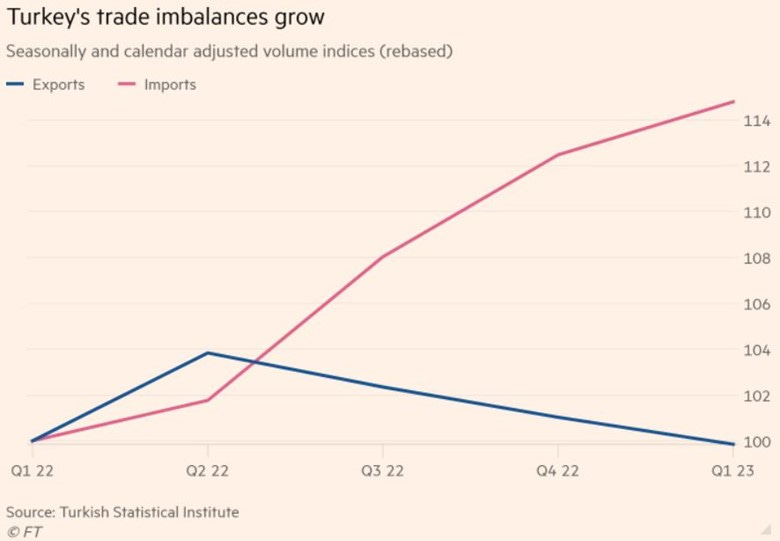

However, persistent structural imbalances in the Turkish economy have left the country vulnerable to shocks. While Turkey’s resilient growth can indeed be attributed to Erdogan’s loose fiscal and monetary policies, it has also added more fuel to an existing inflation fire. Erdogan justified a controversial cutting of interest rates from 19% in 2021 to 8.5%, with the idea that lower rates could lead to lower inflation by delivering economic growth despite an above 40% inflation print – much to the ire of classic economists. This meant that “real” inflation adjusted interest rates were deeply negative, which has led to the widening of trade imbalances and weighing heavily on the currency. On top of this, during the run-up to the most recent elections, Erdogan not only hiked public sector wages, but gave cash handouts and free gas. He also spent billions to re-construct damages from the earthquake in February 2023, while the CBRT has depleted its reserves to support the Lira.

Early economic success for Erdogan stutters

The AKP came to power in 2002 after a crisis and implemented urgent reforms from an IMF package, which included conditions around central bank independence, public deficit and debt reduction, and public procurement rules. These reforms improved inflation, growth, and inequality.

Turkey recovered quickly from the 2007-09 crisis, but faced policy mistakes and external shocks that hurt its stability and credibility. The country is facing a severe economic and political crisis with high inflation, low growth, a weak currency, and a large external debt. The pandemic, geopolitical tensions, the 2023 earthquake and Syrian refugees have worsened the situation.

The AKP has mismanaged monetary and fiscal policy. It has avoided raising interest rates to fight inflation, fearing lower growth and popularity. It has boosted public spending and borrowing, which have increased the fiscal deficit and the debt burden.

Meanwhile, there has been a significant deterioration in the rule of law, press freedoms and civil liberties. The AKP has relied overly on construction for growth, which has come at the expense of farming, turning a country that was once self-sufficient in food into a major importer. Education and procurement have suffered from endless reforms. Success in any business in Turkey now requires access to the ruling party elite.

Foreign investors turning away amid global headwinds and poor local conditions

One of the main causes of the crisis is the loss of confidence in the Turkish economy by foreign investors. Many had invested in emerging markets (EMs) like Turkey, attracted by their high growth potential and low interest rates. However, since around 2013, external factors like political instability and a wider pullout from EMs due to tightening US monetary policy have decreased Turkey’s attractiveness to foreign investors. Foreign ownership of Turkish government bonds has fallen from 25% in May 2013 to below 1% in 2023. Similarly, foreign investors’ stock ownership more than halved to below 30%, have pulled out more than USD7 billion from the Turkish equity market.

Source: World Bank, Total FDI (USD billions)

Fresh blood in policymaking to pivot away from AKP mismanagement?

To address these issues, Turkey has appointed new economic policymakers, who have signaled a more orthodox and credible approach. The new team includes Mehmet Simsek, a former finance minister and Merrill Lynch executive, as presidential economic adviser. Also appointed was Hafize Erkan, a Princeton-educated former Goldman Sachs and First Republic Bank economist, as central bank governor. Aside from rate hikes, the new economic team has also pledged to improve fiscal discipline and transparency, and to attract more FDI by providing greater predictability and stability in policy making. These measures are expected to enhance Turkey's growth potential and resilience in the medium term.

However, the market reaction to the rate hikes was somewhat muted as they were seen as insufficient. The CBRT has indicated that it will continue to tighten monetary policy until inflation shows a significant improvement, so potentially more good news to come for exporters. Any halt on the Lira’s downward spiral will hinge on Erdogan giving the CBRT further leeway to hike rates further.

Turkey's fiscal deficit is expected to be high this year, and the country may be at risk of a balance of payments crisis. This could lead to capital flight, a further decline in the currency, and a surge in inflation. For Turkey, a balance of payments crisis would mean a further sharp depreciation in the Lira, making imports more expensive and leading to higher inflation. It would also make it more difficult for the country to service its foreign debt, leading to either defaults or debt restructurings.

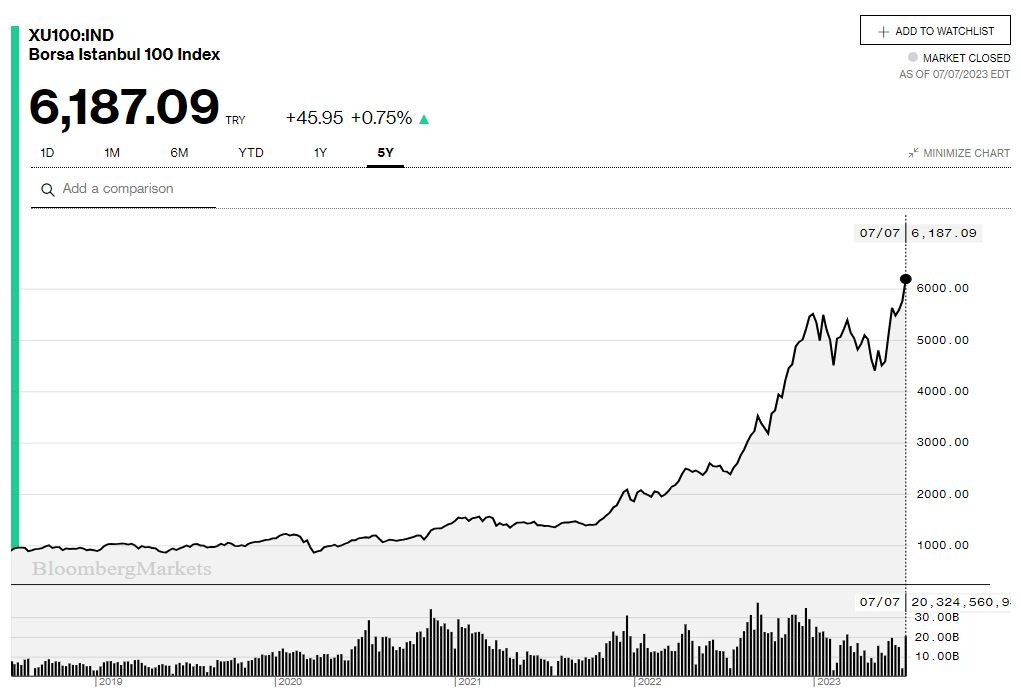

Market to keep tabs on

The new economic policymaking team needs to attract foreign investment, reduce the fiscal deficit, promote exports, manage exchange rate volatility, and further raise interest rates. We don’t think there are any benefits in playing the Turkish equity (despite the recent run-up) or debt markets at the current stage until further rate hikes and other aggressive policy. For now, we keep an interested eye on the country’s developments.

Source: Bloomberg

Companies that are worth looking at naturally would be traditional exporters and producers, which tend to fare better and act as a hedge in the current environment. Tourism players can also benefit from significant currency depreciation. Should the currency stabilize and/or reverse course, we could then shift more towards internally focused domestic names.

While our understanding of Turkey is quite tertiary, the current economic plight has ignited our interest in companies and economic opportunity sets that could come out of this.

After all, we did have the luxury to travel and venture out to Istanbul a few years ago. On that trip, we did take notice of a few names – Turkiye Sise Ve Cam Fabrikalari AS (IST: SISE) and Frigo-Pak Gida Maddeleri Sanayi ve Ticaret AS (IST: FRIGO) look quite interesting now given their large export businesses. The former is a prominent glass company that has consistently demonstrated profitability, but trading at a discount to peers and industrial counterparts, and the latter, a Turkish juice exporter with brand trading at low multiples.

References:

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/22/world/middleeast/erdogan-turkey-interest-rates-economy.html

https://theconversation.com/erdogan-has-wrecked-turkeys-economy-so-what-next-205502

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.CD.WD?end=2022&locations=TR&start=1996

https://www.ft.com/content/1275bbfd-4421-43de-b78d-7f88e056c091