Overview and takeaways on Chinese commercial activity in the Middle East and beyond #7

1 Jul - 31 Jul 2022

CONTENTS

1) Iran, Saudi, and Egypt Make Moves to Join the BRICS – Waning Western Hegemony or Realpolitik?

2) China Shifts Away from US Assets, While Continuing Its Shopping Spree in Yuan

3) Chinese Investments Starting to Pour into the UAE

1) Iran, Saudi, and Egypt Make Moves to Join the BRICS – Waning Western Hegemony or Realpolitik?

Much has been said about the aspirations of several Middle Eastern states to join the BRICS club over the past month. In late June, Russian state media announced that Iran and Argentina had officially filed applications to join the bloc. Interestingly, during Biden’s somewhat unproductive visit to Saudi Arabia, BRICS announced that the Kingdom, alongside Turkey and Egypt were also in the process of making applications to join the bloc. Russia has of course touted the move as evidence that western sanctions have failed to isolate it on the international scene. However, the motivations of these states in making symbolic overtures (for now) are more pragmatic than ideological and may simply be a hedge amid an uncertain future for the current geopolitical and economic world order.

While the BRICS began as a mainly symbolic grouping in 2009 and has often been hindered by the Sino-Indian rivalry, there are signs that change may be afoot. First and foremost, its members clout has swollen since then, with the bloc now accounting for BRICS account for more than 40% of the world's population and about 26% of the global economy.

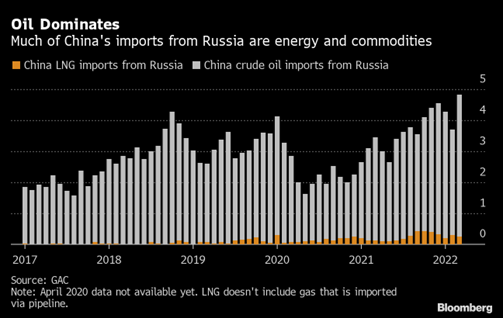

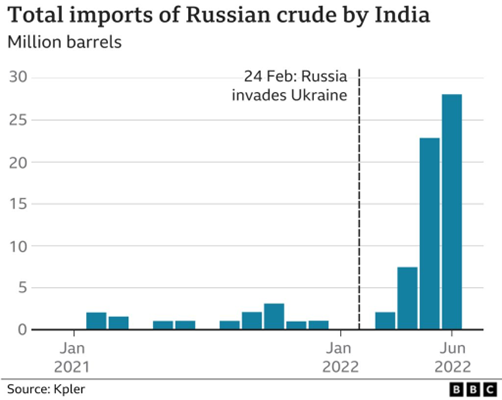

While trade among BRICS states was limited in nature, the new global energy landscape is forcing many developing countries declare allegiances when it comes to Russian oil imports. While many western states have the luxury of perusing ideologically-driven bans on Russian energy imports (which, even still has proven to be tough), in a world of soaring commodity prices this hasn’t been so simple for most countries. China has readily accepted discounted energy supplies from Russia, blunting the impact of western sanctions on Moscow. The world’s second largest oil importer after China, India, has also acted with pragmatism and snapped up discounted Russian crude, much to the disappointment of western states pushing Delhi to take a stronger stance on the Ukraine conflict. There is growing evidence that Russian crude exports to developing countries are being routed through Egypt, Saudi, and the UAE to mask their provenance.

Furthermore, it’s no secret that Moscow and Beijing seek to create an international reserve currency and an integrated inter-bank payments system based on a basket of BRICS currencies to counter Western sanctions. For countries who have not signed up to the western-led economic campaign against Russia, BRICs membership could serve as a hedge to the threat of secondary sanctions by the G7 or NATO. Another notable development was China’s donation of reserve funds to the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB), adding an economic, trade, and development dimension to what was previously a broadly symbolic gathering of leaders.

However, despite Moscow trumpeting the impending ascension of Iran, Saudi, Egypt, and Turkey, to the bloc, among other contenders, the road to membership is by no means simple. Iran’s bid to join the Chinese-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization is telling here – Iran gained observer status in 2005, it looks like it will only gain full membership this year or next. While the NDB is an interesting new development, it is the first of its kind for the bloc and a wider framework for integrating new joiners and forming coherent joint policy may take time to emerge. Middle Eastern countries are well aware of this, and are likely making the overtures to kickstart a process that may one day provide them with easier access to hungry energy markets where western sanctions and dollar hegemony could be of lesser relevance in the long term. In the meantime, the optics look good for Moscow and Beijing, and feeds into a narrative of waning western dominance over the global economy and a redrawing of geopolitical alliances in the decades to come. With China and India increasingly wary of western moves to hinder its access to Russian crude, Saudi and Iran are welcome additions to the BRICS should it become a more cohesive trading bloc with a unified reserve currency.

References

https://thediplomat.com/2022/07/great-power-conflict-fuels-brics-expansion-push/

2) China Shifts Away from US Assets, While Continuing Its Shopping Spree in Yuan

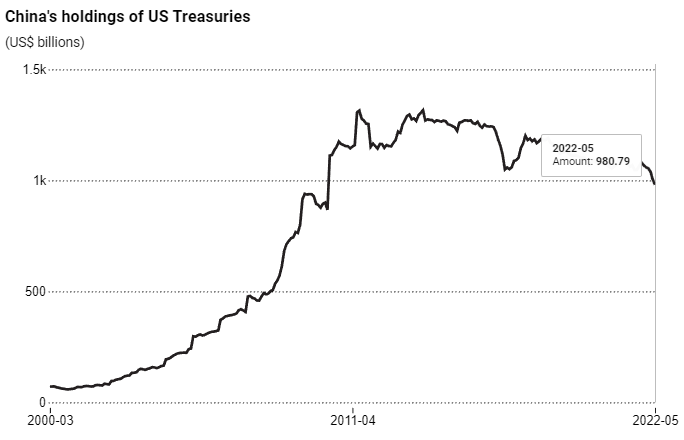

China has aggressively reduced its US treasury securities by 9.3% since November 2021, from USD1080.8 billion to USD980.8 billion in May 2022. US government debt now accounts for around 31% of China’s USD3.07 trillion of foreign exchange reserves, the lowest account since the global financial crisis of 2008.

We have most highlighted Saudi Arabia’s accelerated US debt dumping post-start of the Russia-Ukraine conflict in our previous newsletter. The US (and EU) effectively showed their hand to the world when they weaponized money in March 2022, i.e. by hindering Russia’s access to international forex markets.

As we touched upon Saudi Arabia’s incentive for diversification in our May newsletter. The West throughout history has considered many nations as bad actors, but have not raised the stakes of currency seizures/freezing at a global scale until the Russian-Ukraine conflict. For Saudi Arabia, reducing US financial leverage would mean more room to pursue foreign policy adventures without being policed, as it has been in the past over the Jamal Khashoggi killing or its intervention in Yemen. We see some resemblance with Beijing’s de-dollarization particularly under the backdrop of deteriorating bilateral relations with the US:

“The ability to discredit one sovereign savings incentivizes diversification, which we think is part of the Kingdom’s agenda now. What we are witnessing is the nature of realpolitik, whereby to safeguard a nation’s assets, accrued economic surpluses are not going to be put into place where they can be used against you, especially as tensions rises globally.”

The tension is much higher than before across the Taiwan Strait and de-leveraging should play into Beijing’s advantage should they ever look to undertake “special military operations” abroad under a new legal framework for military protection of foreign interests issued by the government last month. Not only that, as the world’s largest energy importer, it makes strategic sense for Beijing to shift towards buying energy with its own currency given finite dollar reserves. With China’s near-insatiable energy demand, this could be particularly problematic under amid increasing USD energy prices.

Interestingly, on 18 July 2022, Australia’s news.com.au reported that China paid for a shipment of Australian iron ore in Yuan, and not USD. Up until now, we have only seen emerging markets and rouge states sell commodities to China in Yuan. To have Australia, a member of the AUKUS (three-party security pact between Australia, the UK, and US) sell commodities in Yuan may be a sign of things to come, just as Russia is attempting to force European countries to pay for gas in Roubles.

As commodities exporters like the Saudis or Middle East players find difficulty in increasing production (and why should they under artificially higher prices), a shift away from the dollar may prove beneficial because why swap petrodollar revenue for treasuries that are collapsing in value relative to the energy that is being sold.

The trend we have been alluding to over the past several months is that the West’s advantage over financial asset control is starting to be displaced by a new paradigm of commodities and real asset leveraging as imposed by the likes of China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. This is done either out of strategic desire or energy realpolitik necessity; we will continue to flag these developments as they happen.

References:

https://ticdata.treasury.gov/Publish/mfh.txt

3) Growing Chinese Involvement in UAE Financial Sector

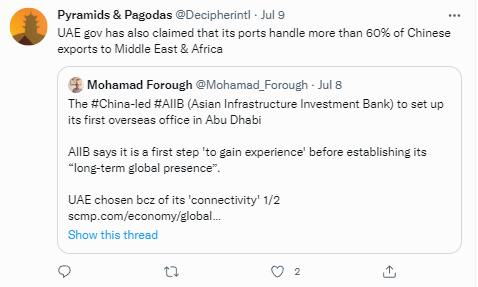

In early July, China-backed Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) announced plans to open its first overseas office in Abu Dhabi. The UAE, one of the bank’s 57 founding members, is set to serve as an interim operational hub for the Beijing headquartered bank to gain experience before expanding its client and stakeholder base regionally. We see this as a logical move with UAE ports already handling over 60% of Chinese exports to Middle East and Africa. Setting up a local hub also provides further connectivity and momentum on commercial and financing activities.

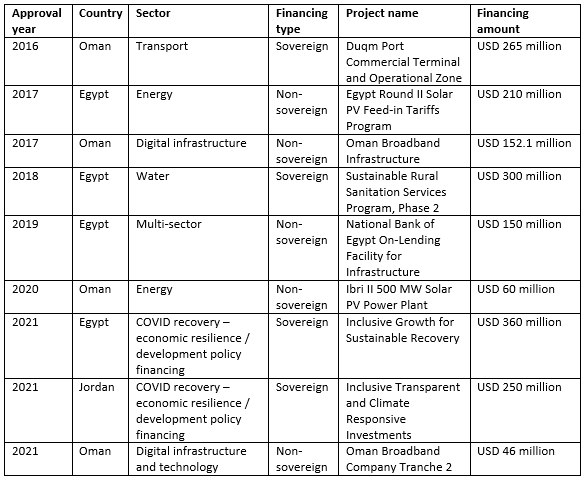

As a formal operational agreement is being put in place, it is worth mentioning that the bank’s developing portfolio already includes 181 projects in 33 countries worth USD35.7 billion. We highlight some of AIIB’s notable approved projects in the Arab world below, which excludes multi-country projects:

Many of the investments made over the past six years have been focused on traditional and digital infrastructure across Arab states. In line with many of Beijing’s moves to shape the global economy, expanding AIIB’s footprint in Abu Dhabi is one of many steps to challenge the Western-led World Bank, IMF, and Asian Development Bank influence in the region and to further prop up China’s Belt and Road initiative. While the AIIB’s close involvement with the BRI has sparked concerns in the West, it has claimed that the PRC government has a minimal role in decision making at the bank.

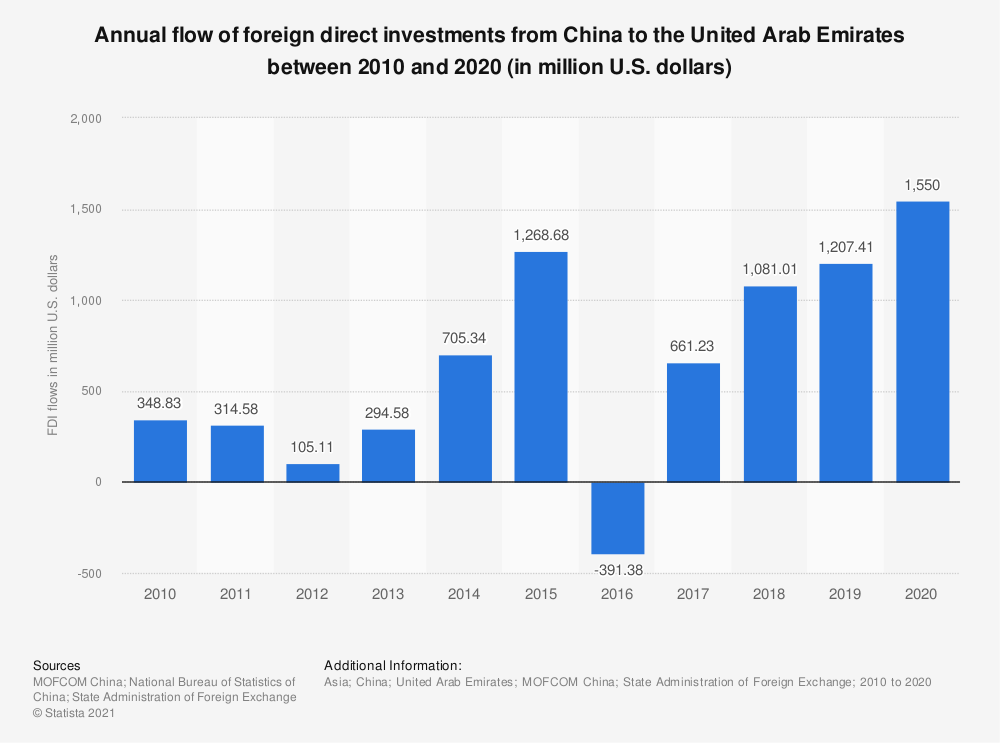

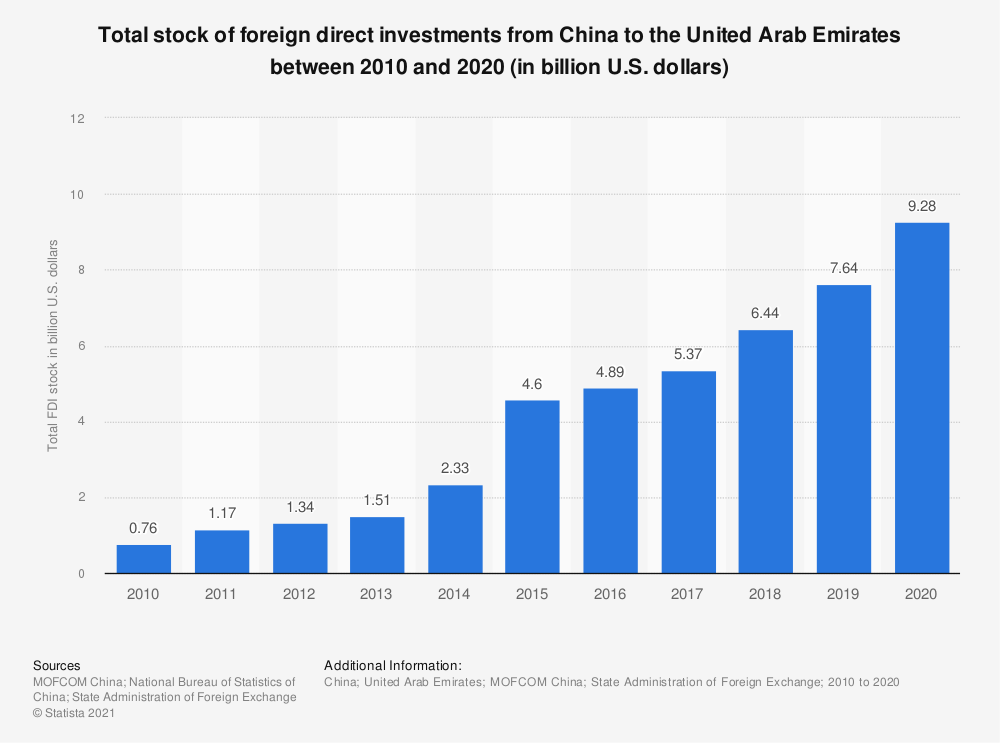

We further note that annual flow of foreign direct investments from China to the UAE has increased from USD 348.83 million in 2010 to USD 1.55 billion in 2020, while total stock of foreign direct investments from USD 760 million to USD 9.28 billion for the same period.

That said, it is not all a one-way street; Chinese state banks have recently been tapping into Gulf investors last month. Nasdaq Dubai listed 5 tranche carbon-neutral themed bonds worth USD2.68bn by ICBC. ICBC Dubai branch was responsible for the issue, and interestingly it was Yuan-denominated. It is a move that strengthens bilateral cooperation between the UAE and China in capital markets, and Chinese banks in the region.

References: